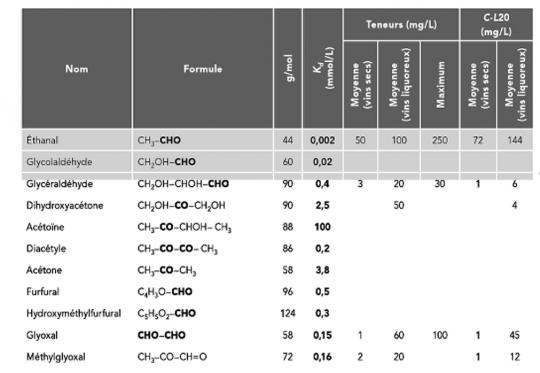

In the table below, the key parameter is the dissociation constant Kd. The lower the value, the more the SO2 combines and the more difficult the reaction is to reverse. Note that the combination with ethanal is fixed. However, this is less the case for diacetyl and not at all for acetoin. A distinction is then made between releasable combined SO2 and blocked combined SO2.

In the case of diacetyl, the total SO2 combined with the latter will be released when the free SO2 level in the wine drops.

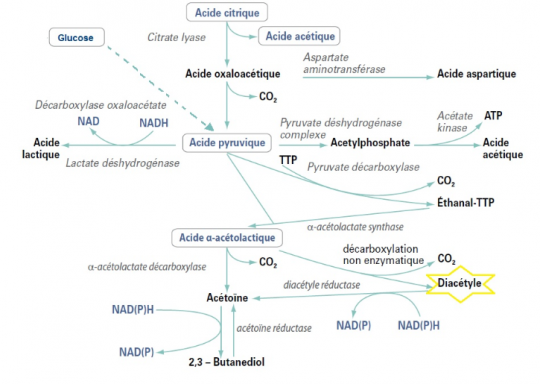

Ethanal is produced by yeast during alcoholic fermentation. Lactic acid bacteria (or most of them) are able to break down ethanal into ethanol. This happens at the beginning and end of malolactic fermentation. In the middle, the bacteria are concentrated on the malic acid.

Various situations can be considered for the optimization of the amount of sulphites used.

Case 1: Alcoholic fermentation is immediate and rapid, like the MLF.

In this case, the ethanal produced by the yeast will be rapidly transformed into ethanol by bacteria. Similarly, diacetyl production at the end of MLF will automatically be consumed by the yeast's residual activity, which is still significant. Very early sulphiting is feasible here since the environment is rapidly cleansed with few combining molecules.

Case 2: Malolactic fermentation is longer and/or sluggish.

Residual yeast activity is then reduced. This is often the case when the goal is "thorough completion", i.e. breaking down the ethanal as much as possible, breaking down the citric acid producing diacetyl and waiting for it to be broken down into butanediol/acetoin.

The idea is then to have an MLF that goes quite far in breaking down the compounds. For it to be effective, it must be kept on lees to benefit from residual enzymatic activity (diacetyl reductase). Be careful that the wine does not become too cold, otherwise enzyme activity will decrease.

This solution is obviously riskier than the previous one because a whole host of elements can be broken down at this stage (citric acid, tartaric acid, and pentoses among other things). This can lead to an increase in volatile acidity.

Although this risk is present, it is rare, especially since the lag time does not exceed 15 days after the end of MLF. This delay is often enough time to decrease turbidity prior to transferring the wine to barrels.

Case 3: Residual sugars remain. In this case, malolactic fermentation is no longer driving the decision to sulphite. A vat starter should be prepared to break down the remaining sugars.